CASE Filed with Supreme Court – SEBI v. Abhijit Rajan

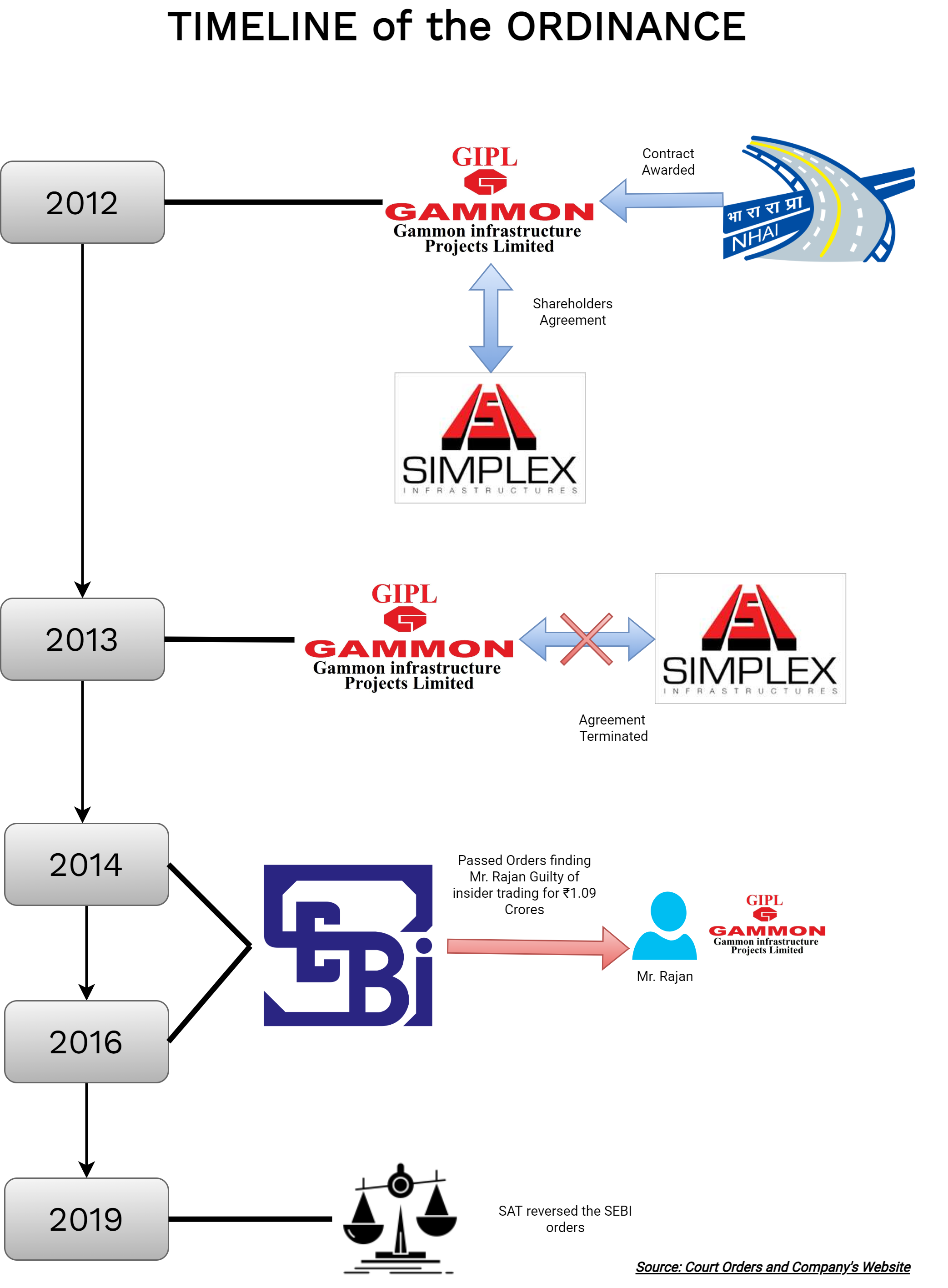

Mr. Abhijit Rajan was the Chairman and Managing Director of Gammon Infrastructure Projects Limited (GIPL). In 2012, GIPL was awarded a ₹1,648 contract by the National Highways Authority of India (NHAI) to set up the Vijayawada Gundugolanu Road Project Private Limited (VGRPPL).

GIPL entered into two shareholders agreements with Simplex Infrastructures Limited (SIL) that had been award similar projects in other states. Under these agreements, GIPL was to invest in SIL’s entity towards road projects, and in turn, SIL was to invest in VGRPPL such that GIPL and SIL would hold 49% equity interest in each other’s projects.

In 2013, the GIPL Board of Directors led by Rajan decided to terminate the agreements, and he subsequently sold his shares in GIPL prior to announcing the said termination publicly. This transaction came under the scanner of the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI).

SEBI in 2014 and 2016 passed orders finding Rajan guilty of insider trading to the tune of ₹1.09 crore, which was reversed by an SAT in 2019, leading to the present appeal before the apex court.

A Securities Appellate Tribunal (SAT) order ruled that the sale of shares by former Gammon director Abhijit Rajan did not amount to insider trading.

“It so happened in this case that according to SEBI the closing price of the stock on 03.09.2013 showed favourable position for the respondent and SEBI was able to calculate as though the respondent made a profit. But if a company is likely to gain strength by making a meaningful change in its policy, the price of its securities is likely to shoot up. Despite such a natural phenomenon, if a person sells his stocks without waiting for the market trend to show up, it can only be taken as a sale, devoid of any desire to make unlawful gains, even if it cannot be termed as a distress sale.“

Thus “As a matter of fact, the Tribunal found that the closing price of shares rose, after the disclosure of the information. This shows that the unpublished price-sensitive information was such that it was likely to be more beneficial to the shareholders after the disclosure was made. Any person desirous of indulging in insider trading would have waited till the information went public, to sell his holdings.“

The SAT had reasoned that the termination decision was not price-sensitive information, that Rajan had needed to make the sale at the time on account of corporate debt restructuring, and that the SEBI had acted based on the closing price of the stock a day after the sale of shares.

Before Honourable supreme court, appearing for SEBI, Senior Advocate Arvind Datar argued that statutory prohibitions cannot be diluted on the basis that the total value of the contracts terminated was only a minor percentage of its turnover.

He added that bona fide intentions or grounds of necessity, as was pleased by the respondent, cannot frustrate the objective of a strict ban on insider trading practices. Further, since the stock exchanges were only intimated about the termination towards the close of trading hours, SEBI considered the closing price the next day.

Advocate Somasekhar Sundaresan, appearing for Rajan, argued that the appeal did not raise any substantial question of law, and lack of sale of shares would have led to GPIL’s bankruptcy. He pointed out that every rupee of the transaction had gone into corporate debt structuring.

The Bench at the outset noted that the price sensitivity of information is directly correlated to the ‘materiality of the impact’ it can have on the price of the company’s securities.

“An information may materially affect the price of the security of a company either positively or negatively. The impact may be beneficial or adverse. The information should have the potential either to catapult the price of the securities of the company to a higher level or to make it plunge. The effect can be bullish or bearish. But the effect should be material and not completely insignificant.“

The Court explained that while the SEBI (Prohibition of Insider Trading) Regulations cannot provide an ‘escape route’ for those indulging in insider trading, normal human behaviour cannot be ignored.

“If a person enters into a transaction which is surely likely to result in loss, he cannot be accused of insider trading. In other words, the actual gain or loss is immaterial, but the motive for making a gain is essential.“

The Appellate Tribunal was right in holding that the respondent had no motive or intention to make unlawful gains given that his actions were on account of the pressing necessity of an imminent bankruptcy, the Court stated.